PDF printable version (in Italian)

It was just after eleven o’clock, and the man, exhausted after a day of reporting and various annoyances, had put on his blue and gray pajamas, gone to bed, and was about to turn off the light to enjoy that long-awaited rest.

However, as soon as he turned toward the door, he noticed a strange glow, like glitter sprinkled on the furniture and wall. He crinkled his eyes, closed them, and opened them again, but that strange effect was always there, like a swarm of fireflies in a summer meadow.

Being too tired to investigate, he gestured with his hand as if to chase away that distraction and hit the abat-jour switch. Darkness ended the shimmering, and the Ludovisi, thinking he had been seeing things through, ran a hand over his forehead and muttered, “I’m really in a bad way!”

Just as he sank his head into the pillow, he almost risked his skin: a full-length, well-dressed figure with the aristocratic features of his former partner Melucci appeared before him, just as if she had been flesh and blood.

The accountant jerked as he bumped against the headboard and felt his heart throb wildly, “But… But…” he began to stammer. “He can’t … No … No!”

After that, without making any other sound, he fell unconscious and spent the entire night in that state.

When he woke up the following day, he felt groggy as if after a drunkenness and, resting his feet on the ground, was struck by a violent dizziness. “It must have been a bad nightmare,” he said. “I’m really in a bad way…”

He wore his flannel robe and slowly went to the kitchen to make coffee. As he entered the room, heading toward the stove, he noticed a folded paper on the table.

“I did not leave him there last night,” he thought, puzzled, with his vision still blurring.

That sheet of thick, slightly amber-colored paper, not only had he not laid it down, he had never even had it in his hand. He took it, observing his arm trembling and goose bumps appearing as a sudden irritation.

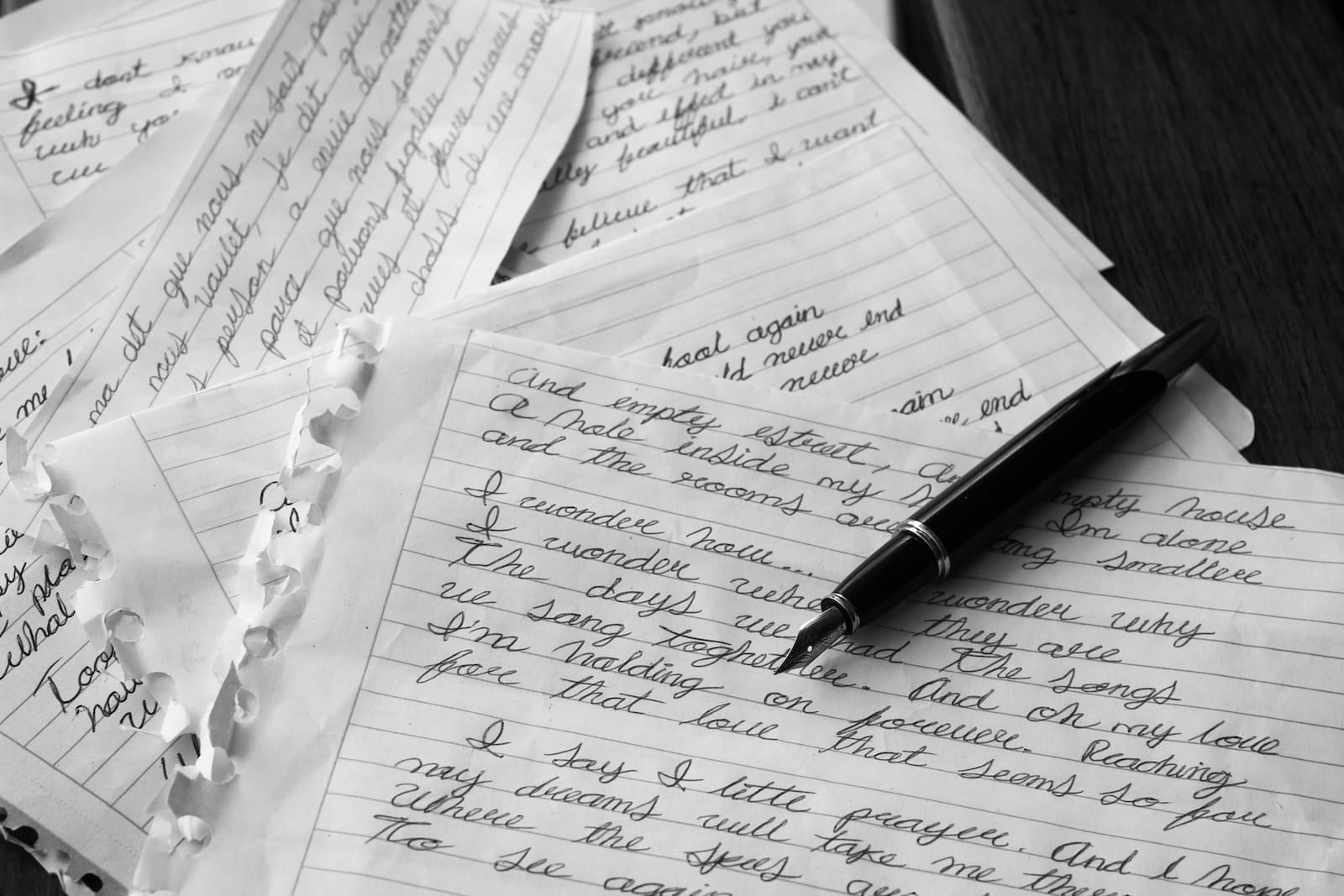

It was written in his handwriting, in beautiful calligraphy, and carried the following letter:

“Dearest Amedeo,

Ever since that heart attack crushed me, a weight has been weighing on my conscience: the only trace of humanity that still lingers about me. I should have confessed my guilt to you earlier, but I’ve been licensed to do so now… Forgive me for last night; I know I terrified you; that’s why I preferred to leave you this paper so that you would know that I feel only disdain for my mistakes. I confess: I stole money from our society. I used to be able to do this through fake orders and other financial devilry, but know that I came to such indecency only out of necessity, to pay debts that still live on, even though I am dead and buried. It is all in your hands now, and I am sure you will be able to manage to the best of your ability an activity that you had conceived and, therefore, deserve to direct without interference.

I sincerely wish you health and luck,

Your (I hope still) brotherly friend Lorenzo.”

The paper fell from his hand just in time for him to lean back in a chair. Everything revolved around him, and fear again made his heart race like a bolted horse. He managed to move slowly until he reached a water bottle. He downed several sips, wetting his entire robe. Then he let go of the table and closed his eyes so he could no longer see that swirling succession of images and sounds.

He stood motionless for about ten minutes, unable to reason.

“It’s not possible … No … It’s not …” he repeated like a jammed record player. “No…”

At eight o’clock, the woman who helped him with housework rang punctually at his door.

“I have to open to Angelina,” he thought as he returned erect, “Otherwise, she’ll think I’m sick.”

He got up and staggered to the entrance, turned the key with difficulty, and lowered the handle. He did not have the strength to do anything else. He remained motionless, waiting for her to push in.

“Ragionier Ludovisi!” the woman exclaimed as soon as she saw him as waxy and impaled like a salt statue. “But are you feeling all right? Do you want me to call a doctor for you right away?”

“No, don’t worry,” stammered the man who feared doctors more than the plague. “Go about your business.” Slowly, with bated breath, he headed for his study.

The woman watched him walk, dragging his feet as if his legs weighed more than his entire body. She couldn’t stop herself from repeating, “Accountant, you don’t look well to me… However, if you have any problems, call me…” and began to tidy up the few things left out of place in the living room.

In the meantime, the man had entered the small room used as a study and was pacing back and forth, making a noise of trampled paper. Angelina, an uneducated woman from school but made wise by a life of sacrifice, hearing that very unusual pattering, looked out the door and saw accountant Ludovisi standing in front of the glass of the French window, surrounded by dozens of papers crumpled up and thrown on the floor.

“My, what a mess!” he exclaimed upon seeing the room in that state.

Ludovisi did not even turn around, as if he had not heard those words, “You go ahead and do your chores, Angelina. I am fine.”

“I’m doing it, accountant,“ he replied, picking up all the papers abandoned on the floor.

“But there is nothing to do here. You’re going to rearrange my bedroom. I think I’ll lie down for a while to rest.”

In contrast to the daylight, Angelina looked at that figure, and it seemed almost ethereal, luminescent like the glow the man had seen the night before.

“In my opinion, she is not well,” he added. “Anyway, let me pick up all this garbage, and then I will prepare your room.”

He began collecting the papers and placing them in a flap of his apron. She was not a curious woman, but the temptation was far more robust than she was: she opened a pair randomly and noticed they were identical. It was a draft, perhaps never completed, of a handwritten letter in Ludovisi’s handwriting. He began to read it while squinting:

“Dear Lorenzo,

Your passing was a hard blow to me. Not only because I lost a loyal friend but primarily because of the suddenness that did not allow me to catch up with your good faith. Unfortunately, as you know, I lost a considerable fortune gambling and, without even fully realizing it, ended up in the hands of a loan shark (whom you know well…), who demands a deposit every week. I was desperate, Lorenzo. Desperate.

For this reason alone, and taking advantage of your trust, I rigged several accounts and embezzled liquid capital from the company. After your heart attack, it was as if I had died too… Maybe it was right for me to die, instead of you, for that rotter to kill me, to whom I still owe much more money than he lent me… I’m sorry, dearest friend. I’m sorry…“

At the end of the reading, Angelina emitted a slight mumble as if what she had just understood was far more sadly familiar to her than to Accountant Ludovisi.

“Don’t torment yourself,” he said as he approached the man. “If we were never wrong, we wouldn’t even be human beings!”

Amedeo turned slowly, like a puppet operated by an automatic mechanism. His eyes were glassy, as deep as lightless caverns.

“I saw a ghost,” he whispered as if he lacked air. “And he even left me a letter and saw a ghost, Angelina!”

The lady gently took him by the arm, “Accountant, you are confused and not feeling well. Go rest in your room. I will tidy it up in the afternoon.”

The man, who seemed to be aging fast, did not respond. He was motionless, paralyzed by a fear that rose from the emptiness of his being. In a low voice, he looked at Angelina and asked her, “Did you read the letter in the living room, too?”

“There is nothing in the living room. I peeked at the bad copies here,” the woman replied demurely.

“But what does it say? There is no such thing as a bad copy! Are you kidding me, Angelina?” exclaimed the accountant, with the veins in his forehead throbbing. “It’s that way. Melucci wrote it tonight. I recognize his stroke perfectly.”

“Melucci?” exclaimed Angelina. “But isn’t he dead?”

“Exactly…” sighed the man.

For a few moments, only breaths were heard, the intermittent hum of the freezer.

“There is nothing in the living room, accountant… I think you are confused, and all these papers prove it… Go lay down; I will take care of tidying up.”

“That way. That way, Angelina,” Ludovisi repeated mechanically. Then, turning back to his pale reflection on the glass streaked with dust and drizzle, he added, murmuring, “Don’t worry about me. Just go back to your chores.”

Photo by Ire Photocreative

Filed for legal guardianship with Patamu: certificate