Since I was born, I have been immersed in a “middle ground,” suspended between art and the craft of ceramics. The Italian town where I came into the world and grew up until my teenage years, called Caltagirone, is located in the southern part of the province of Catania (Sicily), atop a hill about 650 meters high overlooking a typically barren surroundings in the northern part and, less steep and arid, in the southern part.

Ceramics: between traditional culture and artistic spirit

However, this seemingly anonymous town in the Sicilian hinterland, famous for its very long staircase of Santa Maria del Monte (also wholly decorated with ceramic tiles), has also always been renowned for its long tradition of majolica making (often called “artistic ceramics” to distinguish it from industrial ceramics).

Caltagirone, UNESCO heritage site for artistic ceramics

Along the narrow streets (in dialect, “carruggi”) of the historic center, there have always been dozens and dozens of artisan workshops in which ceramists who were the sons of ceramists created their works, taking care of every step of the process: from the purchase of raw materials to the wrapping in newspaper sheets of the pieces sold. My paternal family belonged to this category, and, without any vainness-unjustified; moreover, since this tradition has ended, I can say that it has enjoyed unparalleled notoriety in the surrounding area and different parts of Italy.

When I was still crawling in the large house of my paternal grandparents, the ground floor of which was used entirely as a workshop and for the exposition of artifacts, I moved among dozens of figurines, panels for hanging, plates, vases, and any other creation that might appeal to even the finest palates in Caltagirone. Both my grandfather (my namesake from the “holy name“) and my father Raffaele (who, after the Academy of Fine Arts in Rome, alternated between teaching art history and creating ceramics) followed the highroad that skirted, on the one hand, the craft culture handed down over the centuries and, on the other, artistic research and ever new forms of expression.

Expressive forms of artistic ceramics of Caltagirone

As is often the case in such cases, the culture of a place defined rules and de facto standards that, as the years went by, were transformed from innovative gimmicks into actual characteristic patterns. In other words, what was proposed by a potter, if considered pleasing, could slowly spread and become a modus operandi that became part of the local craft tradition.

This tradition includes floral patterns based on repeated patterns and shapes resembling colorful bird feathers. In addition, Caltagirone’s potters, remembering, more from history books than in practice, the Arab domination, often did their best to make vases of anthropomorphic form, depicting the so-called “Moors” or sometimes even female characters and knights in the Norman tradition.

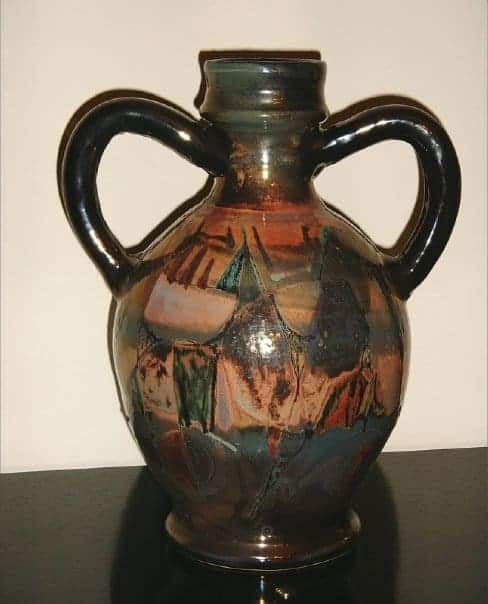

Despite the prevalence of these “standards,” my family has always devoted itself to very original artistic research, avoiding approaches that, while honoring tradition, sacrificed creativity. All the photographs in this post (except for the vase with “typical” motifs – a gift for my parents’ wedding) represent majolica made by my father and grandfather.

The making of majolica tiles through the eyes of a child

Before discussing other details, it is worth devoting a few lines to making majolica tiles. I must preface this by saying I have never participated “seriously” in these activities. Still, my continued attendance at the workshop is enough to have given me a reasonably thorough knowledge.

The raw material for majolica is clay collected in the Caltagirone area, purified, and consolidated into homogeneous blocks ready for sale. All potters reformed at local suppliers who sold parallelepiped-shaped blocks with a length of about 60 cm and a base of about 20 x 20 cm. I remember a stack of them ready for use in a laboratory corner.

Once the subject of the work was defined, a block of clay was cut (using the simple but highly effective method based on a thread as thin as a violin string) and brought to the work table. All creativity was unfolding in that dirty microcosm, full of tools, pots, jars, pictures of models stuck on the walls, and an ever-present little radio always on.

A job as delicate as that of a watchmaker

In contrast to marble sculpture, which proceeded by subtraction and, alas, was often irreversible (although Michelangelo was able to avoid a few “disasters”-as in the case of the Moses preserved in the church of S. Pietro in Vincoli in Rome – with skillful stratagems), clay modeling was generally a process that proceeded from the individual parts and proceeded by addition.

Of course, excess clay also had to be removed, but more often than not, they would create small pieces of various shapes to make a hair, now a finger, and so on. The process was meticulous, and the level of detail depended greatly on the potter’s creative idea. When you wanted to make, for example, a realistic figurine, it was necessary to take care of details of even a few millimeters. Whereas, if one wished to transcend the “verist” model (much appreciated in Caltagirone) and take refuge in the kaleidoscopic world of an abstractionism “without excesses of a license,” one could proceed with more incredible speed, attending more to the whole than to individual details.

From clay to artwork

Once the artifact was complete, it was left to dry for several hours. As the clay lost water, it became solid but highly brittle. At that point, the first firing could be done to obtain “terracotta” in the jargon. From dark gray, the object acquired a color between brown and reddish and became extremely hard and equally brittle.

A great deal of pottery has stopped at this stage, although, in general, these are artifacts of modest value intended for non-ornamental purposes. In contrast, the Caltagirone art potters continued the process with one or more colorings. The most straightforward approach was based on “cold” or “dry” chrome plating, which spread an opaque color directly on the clay. The result, very characteristically, was very pleasing, with hues that faded into a pastel hue but, at the same time, had no sheen.

The most elaborate processes

If, on the other hand, a brighter result was desired, a significantly more laborious chrome-plating process was required. The terracotta object was, first of all, glazed white. It was dipped into a vat containing liquid paint until it soaked, cleaned up, scraped the glaze from the supporting parts, and left for a few hours to dry.

It was baked and baked for the second time as soon as it was ready. The result was a completely shiny white artifact that had wholly lost the porosity of terracotta. With this stratagem, a chrome plating could be made that would be brilliant and a thousand shades of hue.

The color “miracle” in progress!

The colors used at the beginning of this third phase were called “lustri” in dialect slang and appeared as liquids of a metallic nature (including pure gold) of a grayish-purple color. It was impossible to distinguish whether it was a blue or a red at that stage, so considerable care was required. Once the new color layer was applied, they would wait a few more hours and then inform the pieces for the third (and final) time.

The high temperatures melted the colors, revealing their chromatic and luminous character. In addition, the inevitable smudges gave rise to unintentional and unique decorations that gave the object a modern character while respecting the Calatino tradition’s main characteristics.

Not just vases or plates for hanging

The Calatino tradition is firmly based on “classical” objects, such as plates, vases, or decorative figurines of various kinds. However, as was often the case in other areas of the fine arts, many cues came from religious tradition — nativities, Madonnas with children, angels, crucifixes, etc., filled entire walls.

It is safe to say that, up to a certain period, almost all Calatinians owned at least one small religious artifact made of majolica, whether it was an ornate stoup, an angel (also called”putting”), or a crucifix to be used as a bedside table in the bedroom.

The typical approach of Caltagirone ceramics.

But unlike Via San Gregorio Armeno in Naples, also famous for its nativity figurines, Caltagirone honored the more classical tradition. Artisans were not looking for photos of political and entertainment figures to make new and original (obviously also decontextualized) nativity scene states. In addition to the Holy Family and animals of evangelical memory, the protagonists were always pastoral and, as if to actualize the episode, they almost always dressed in a “modern” way with pants and smocks.

There was no lack, of course, of all those items that were appreciated by the faithful. In a historical and cultural context where the Catholic church played a central role in everyday life, families did not limit their contact with the sacred only to participation in religious ceremonies but often wished to have at home small “altars” (typical of devotions to holy particles or the Virgin Mary) and holy water fonts where they could keep half a glass of holy water to make the sign of the cross.

Above the cavity into which the holy water was put were usually scenes with angels or baby Jesus. Small compositions in bright colors and sometimes full of drapery animated the bas-relief, giving it a delicate movement, similar to a spiritual breeze that brushed against the forehead of the worshipper.

Space for experimentation

Although the tradition of Caltagirone has always been deeply rooted and has often conditioned the production of ceramics, my family has often distinguished itself through artistic experimentation of various kinds. Among these, a prominent place is occupied by the so-called “fumi,” which came into play during the final firing of the object.

A powdered cartridge of color similar to a firecracker was prepared, and after a few hours of firing, it was carefully dropped inside the kiln through a hole in the top. Given the very high temperature, the cartridge would burst, and the color (a mixture of different powders) would spread all over the firing objects, solidifying and becoming shiny.

The result was very often astounding. The primary decoration blended with irregular patterns in more varied hues, resulting in a translucent patina that changed color depending on location and lighting.

This was, of course, a technique that was as innovative as it was risky, for the result was in no way controllable. Nonetheless, most pieces that have entered my past are endowed with a fascination that transcends the often narrow limits of pure tradition to enter the pantheon of figurative artfully.

Summary of the history of Sicilian majolica

Majolica is a type of tin-glazed pottery that originated in the Middle East and spread throughout Europe during the medieval period. It arrived in Sicily during the Norman occupation in the 11th century and soon became an integral part of the island’s artistic tradition.

Sicilian majolica’s vibrant and colorful designs reflect various influences from various cultures, including Arab, Byzantine, and Norman. The intricate patterns depict a rich tapestry of motifs such as flowers, fruits, animals, and geometric shapes, all skillfully hand-painted on the pottery.

Sicilian majolica has gained popularity over the centuries, becoming a symbol of Sicilian identity and a vital craft industry. Pottery was used for decorative purposes and everyday objects such as plates, bowls, and vases.

Caltagirone, located in central Sicily, is renowned for its majolica production. It has been a center of ceramic crafts since the 17th century, with many workshops and kilns still active today. The splendid Santa Maria del Monte staircase, adorned with colorful majolica tiles, testifies to the city’s devotion to this ancient art form.

Creating majolica involves several complex steps, including shaping the clay, applying glaze, and hand-painting the designs. Each piece is meticulously crafted by skilled artisans who have inherited their techniques and knowledge from previous generations.

Today, Sicilian majolica continues to enchant locals and visitors alike. It is not only considered a beautiful art form but also a cultural treasure that embodies the history and traditions of the island. Owning a piece of Sicilian majolica is like owning a small part of Sicily’s vibrant heritage.

In summary, the history of ceramics in Sicily is a tale of artistic excellence and cultural significance. From its origins in the Middle East to its burgeoning presence on the island, Sicilian majolica has captivated the world with its intricate designs and vibrant colors. It is a testament to the craftsmanship and timeless beauty thriving in the Sicilian ceramic tradition.

Conclusions

In this brief roundup, I hope to have summarized most of the peculiar aspects of artistic Calatino ceramics, particularly those made by my family. This cultural heritage is worthy of preservation, enhancement, and transmission to new generations.

The nobility of Caltagirone’s majolica sculpture is no less fascinating than the much more highly rated marble or bronze sculpture. Still, the care, process, and pride in displaying their creations make Caltagirone majolica a boast that fears no comparison.

Art should not set limits for itself except those of aesthetics, the nature of which, however, is highly variable and subject to more or less drastic revolutions. Majolica lives in the limit between tradition and innovation, letting new ideas flourish and reevaluating what the ancestor masters left to posterity.

Calatino ceramics, therefore, is not and must not be a local product, confined to a circle of villages, but must globalize, overcome barriers, and establish itself in its own right as a living, vibrant art transported by the desire to communicate a most noble and precious reality to anyone who has the sensitivity to receive it.

If you like this post, you can always donate to support my activity! One coffee is enough! And don’t forget to subscribe to my weekly newsletter!