Andrés Segovia (1893 – 1987) was unquestionably one of the greatest and most influential musicians of the last century, devoted wholeheartedly to the dissemination of the classical guitar, and, as is often the case in such cases, his fame has become multifaceted, enriched by legends, false attributions and an almost blinding mythologizing, which has made it extremely difficult for many users of his music to exercise critical activity.

In this article, I wish to highlight some peculiar aspects of Segovian work and, at the same time, try to demolish some of the most unfounded myths. As a classical guitarist, I cannot tolerate the spread of superficial and false judgments that permanently harm the music, too. Only by being frank can Segovia be restored to his rightful place and prevent completely wrong ideas from taking hold without anyone working to correct them.

Segovia and the musical heritage for guitar

The first thesis I would like to highlight concerns a judgment I have often encountered: “Segovia is the father of the (classical) guitar as a noble instrument.” First of all, I would like to point out that, in my opinion, talking about noble and plebeian instruments is undoubtedly not an excellent way to start a discussion. Various composers of the caliber of Beethoven and Mahler “ennobled” all sorts of instruments, including them in their symphonies to achieve particular timbres that traditional ensembles did not contemplate.

But even if we accept the juxtaposition between widespread and concert use of the guitar, the problem remains with the veracity of the above statement. Suffraging it lightly is, in fact, not only dangerous to the history of music but also unfair to a variety of composers who devoted their lives to the guitar.

While it is true that this marvelous instrument, given its flexibility, became extremely popular in not overly cultured circles, this does not detract from the fact that, between the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, there were properly “cultured” musicians who published methods, progressive studies, concert studies, sonatas, concertos, etc.

Fernando Sor, Dionisio Aguado, Mauro Giuliani, Ferdinando Carulli, Matteo Carcassi, Francisco Tarrega, etc., are key players in the flourishing of the guitar during the Romantic period. If we also add Niccolò Paganini (yes, the violinist), who loved the guitar, practiced on it, and composed dozens and dozens of concert sonatas, I think it is pretty clear that before 1893, the year of Segovia’s birth, the guitar scene was already very well nourished.

So why do people close their eyes to the evidence and think all the credit goes to the master? While also based on some deductions, the response breaks a lance in favor of Segovia’s hosannas.

The fate of the guitar during and after Romanticism

To begin with, a clarification should be made: the guitar, like many other instruments (piano, primarily), has not always existed in its current conformation. On the contrary, it has undergone numerous changes based on the expressive needs that musicians demanded.

Without doing a historical reconstruction that is beyond the scope of this article, I can say right away that the most famous ancestor of the guitar is one of the most famous Renaissance and Baroque instruments (especially during the early period): the lute. It was not only, to all intents and purposes, a “noble” instrument but also allowed a vast literature of early music to reach us, which nowadays, despite the existence of numerous lutenists, finds its most natural place in the guitar.

The works, to give an example, of Luis de Milán, John Dowland, Sylvius Leopold Weiss, and, most importantly, Johann Sebastian Bach (even if some of them are arrangements of violin partitas made by the computer itself, e.g., BWV 1006a) provide guitarists with a heritage of the highest quality that can only help to ennoble this fascinating instrument and enrich the concert repertoire with characteristic musicality that can captivate even those who do not have a thorough knowledge of the historical period.

However, Romanticism, a period that, albeit eventually, saw Segovia’s birth, elected the piano as the instrument par excellence. Dozens of more or less famous composers traveled to Paris to compose and try to disseminate their works. I am not referring to the likes of Chopin, who seemed destined for the piano from the cradle, but to composers like Albéniz, who, from Spain, came to the French capital and, while eager to “export” the musicality of their homeland, chose the piano without a second thought.

Albéniz’s celebrated suite espanola (containing well-known pieces in the guitar realm as Asturias – Leyenda or Sevilla) was written for the keyboard instrument. However, it contains solid references to the guitar. It is no accident that transcriptions of the suite have become so widespread that many pieces seem to have originated for guitar. Suppose an arrangement of a Chopin nocturne is always a gamble. In that case, Asturias’ guitar version (I say this without hesitation) is musically more “accomplished” on the guitar (where, in particular, the opening and closing arpeggios spread out like a dusky-toned carpet) than on the piano.

From that background, Segovia found himself with an instrument of endless possibilities and a dominant culture that seemed blinded by ebony and ivory keys. There was a very substantial literature of quality works (e.g., Giuliani’s Rossiniane, Sor’s Gran Solo, and, no doubt, many Paganini sonatas), but what Segovia felt was a distinct lack of continuity. Indeed, his present seemed to have transposed the guitar to domains increasingly distant from the grand stages of theaters and, simultaneously, increasingly immersed in the noisy atmospheres of bars and taverns.

Another not minor fact was related to the spread of pop music (hated by Segovia): if the piano had been the stronghold of the Romantics, the guitar (especially in its acoustic versions with metal and electric strings) was gaining a foothold in blues music, jazz, etc. and, a little later, would also become the quintessential instrument of rock music.

It is not strange then that after developing an overpowering technique based on an extraordinary timbral sampler, Segovia faced a far more long-standing problem. While he did not despise the existing literature (although his judgments were often affected by various idiosyncrasies), he understood it was almost impossible to hold a concert in a large hall in Paris or New York with only that repertoire. What the guitar lacked was compositional continuity from “educated” musicians.

For this reason, he began requesting new compositions and transcribing works that, according to his taste, could fit nicely on the guitar. In that sense, it must be said that his work was remarkable and certainly worthy of praise. Despite his somewhat rigid mindset, he was able to persuade several composers to write new music for the guitar, thus, in a short time, enriching the stock available to concertgoers.

It is also true that his less-than-easy character (paradigmatic is the case of his relationship with Barrios, whom he unsuccessfully asked to dedicate to him the sonata “La Catedral” and which, out of spite, he decided not only not to play but also to discredit with all his students) and his lack of interest in atonal experiments (which were becoming increasingly popular) led him to isolate altogether many works that would only be rediscovered later, but this does not detract from the fact that without his efforts, the classical guitar would never have taken off again.

Segovia and guitar technique

Another controversial aspect concerns the guitar technique. In this sense, it should be clarified that Segovia did not invent anything dramatically different from what had already been established. In the nineteenth century, composers such as Aguado and Sor published their methods, explaining the fundamentals of the technique, even giving rise to a diatribe over fingernails (Aguado was in favor, while Sor preferred “bare” fingertips).

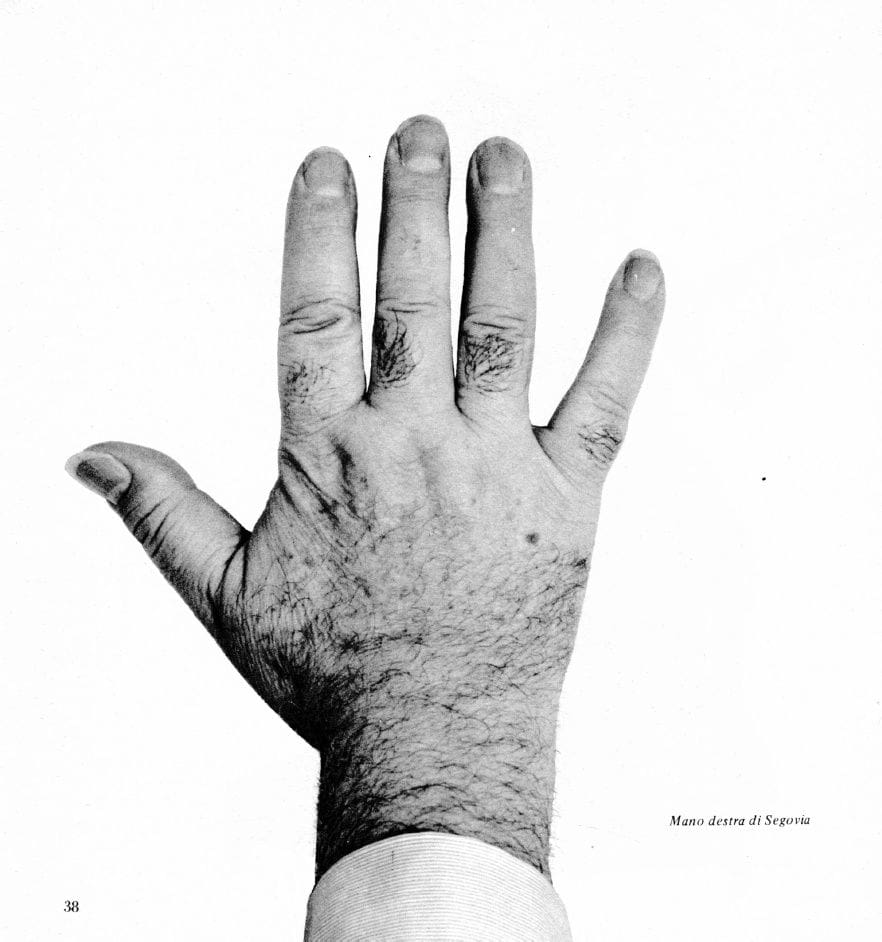

What Segovia did was to study such fundamentals and “discover” elements that, on paper, could only be described in a very sketchy way. In particular, the most outstanding merit was related to timbre research. He understood that the best results could be achieved with relatively short nails, such that the strings could be struck but, at the same time, soften the touch, if necessary, with the fingertip. In addition, Segovia developed a keen ability to move his right hand from the pit to the bridge to achieve rapid timbral changes.

His distinctive sound (an average ear recognizes it immediately) resulted from several factors that stemmed not from technique per se but from exploring the possibilities offered by the instrument. It is, therefore, inaccurate to attribute to Segovia elements of setting already found in earlier musicians. Still, it is correct (on the assumption that there are no recordings of Sor or Giuliani) to say that his emphasis on timbre was a distinctive element that contributed significantly to his worldwide success.

In addition, Segovia welcomed the proposal to use nylon strings (“bare” for the treble three and metal coated for the bass). This new “configuration” allowed him to increase the timbral range of the guitar with a “vertical” differentiation (the bass voices already sounded darker, while the treble was brighter) that proved exceptionally fruitful, especially in the performance of polyphonic music (e.g., Bach or Scarlatti).

The Segovia School and the “Segovians”

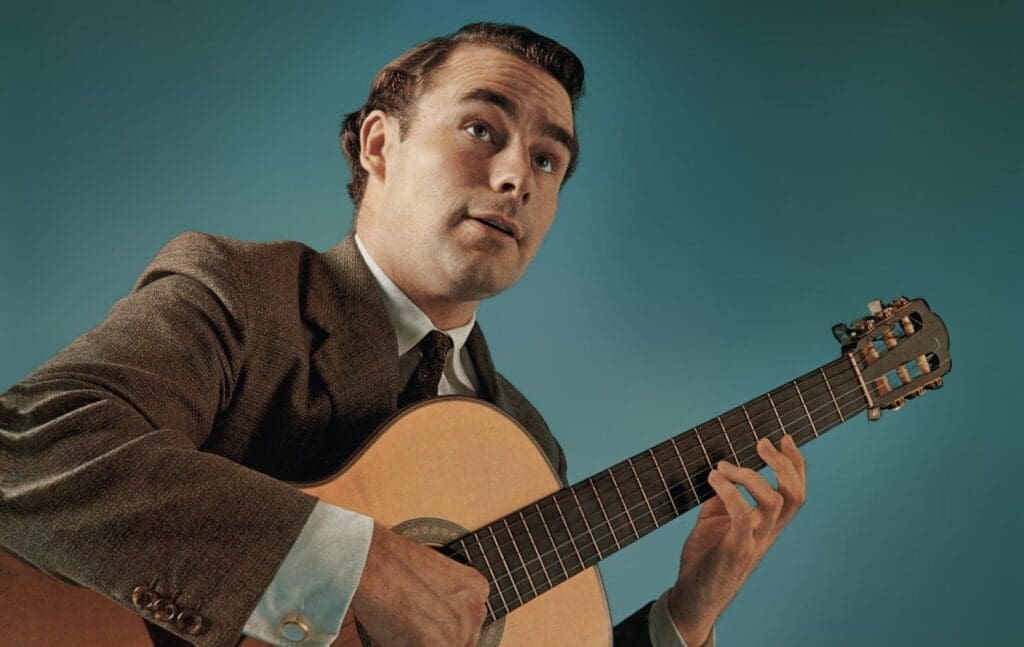

A key chapter in Segovia’s life concerns his teaching activities. Although he never taught permanently in a conservatory, the master often held master classes where some of the most famous guitarists trained (e.g., Julian Bream, John Williams, Eliot Fisk, Cristopher Parkening, Oscar Ghiglia, etc.). Is it then correct to speak of a lineup of “segovians”?

In my opinion, there is nothing more wrong. This is one of the most rugged and dangerous territories to tackle, but I will try to summarize my ideas. Segovia imparted his interpretive ideas to his students, helping them achieve articulation that exploited the guitar’s full potential. However, none of his most distinguished pupils developed an imitative style, neither in terms of sonority nor even in terms of repertoire.

One only has to listen to Bream or Williams to realize immediately that their playing is “unique” and not based on a slavish study of their master’s way of experiencing. In other words, using a metaphor, we can say that Segovia was more of a spark than an actual explosion. The sharpest students learned how to achieve the same richness as their teacher, but they followed the most pleasant path. They were, that is, “segovian,” but not at all segovian (I hope the instrumental use of quotation marks is straightforward).

Unfortunately, while the most talented have been able to enhance the ideas with the right critical spirit, a large group of pseudo-Segovians have begun to “ape” Segovia, focusing mainly on two elements: repertoire and technique. In the first case, the result was a flattening of guitar interpretive production (in a sense, the opposite of what the master desired), with programs that repeatedly seemed to be printed with the same cliché. In the second, you completely misrepresented the teaching of Aguado, Sor, Giuliani, etc., and transited through Segovia, going so far as to hail the most unbearable pedantry.

There are dozens and dozens of guitarists (including yours truly) ready to tell how they spent months of lessons millimetrically adding hand position, reducing or increasing back arching, and so on. All this, as useless as it was harmful, resulted from an attempt at imitation devoid of logical meaning. Instead of systematizing technical concepts cum grano salis, they often preferred to take refuge in a dullness that was indisposed, making central, not music, but a form of postural gymnastics.

Summary biographical note

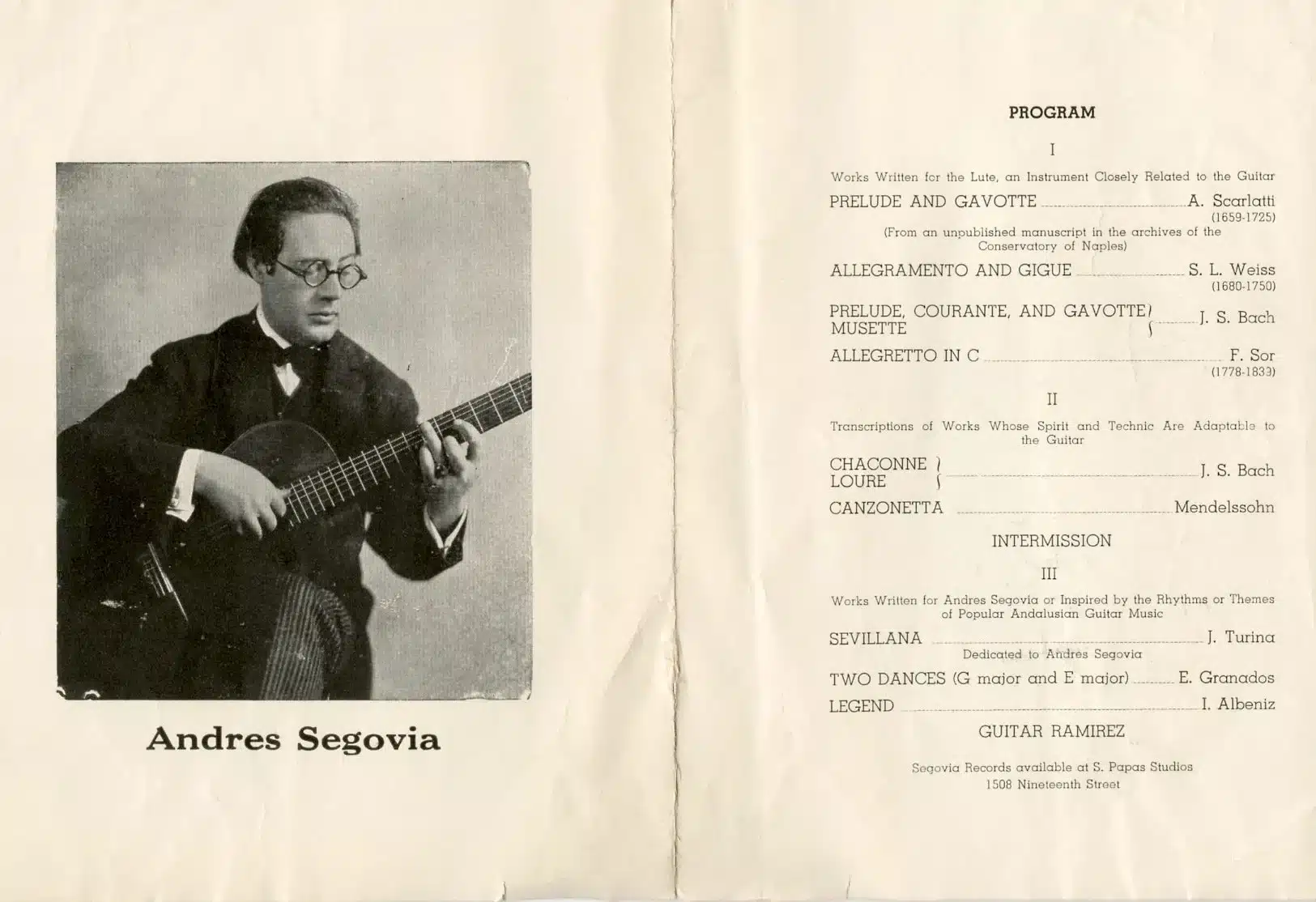

Andrés Segovia, born Feb. 21, 1893, in Linares, Jaén, Spain, was a legendary classical guitarist and composer (although, in reality, his output was limited to a few studies). He is widely considered one of the greatest guitarists of all time and played a significant role in elevating the guitar to a respected classical instrument.

Segovia began playing the guitar at a young age and quickly demonstrated exceptional talent. He received his formal music education at the School of Fine Arts in Granada and later at the Royal Conservatory of Madrid. Despite initial skepticism from traditionalists who believed that the guitar was not suitable for classical music, Segovia’s dedication and perseverance led him to become a pioneer for this instrument.

Throughout his career, Segovia toured extensively, captivating audiences worldwide with his virtuosic performances and unique interpretations of classical, baroque, and contemporary compositions. His exceptional technique, timbre, and playing style set new standards for guitarists worldwide, spawning a generation of “followers” who drew inspiration from his relating to the instrument.

In addition to his extraordinary performing career, Segovia was instrumental in expanding the classical guitar repertoire. He has collaborated with renowned composers such as Manuel Ponce, Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco, and Heitor Villa-Lobos, inspiring them to write music specifically for the guitar. Segovia also transcribed and arranged numerous pieces initially composed for other instruments, demonstrating the versatility and capabilities of the guitar.

Segovia’s influence on the classical guitar extended beyond his performances and compositions. He devoted his life to promoting the artistic and educational value of the instrument. He has organized master classes, taught countless students, and written instructional books that have become essential resources for guitarists.

Andrés Segovia’s contribution to the guitar has earned him numerous awards and honors, including honorary doctorates, knighthoods, and the prestigious Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award. His legacy inspires generations of guitarists, and his recordings remain prized classics in the classical music world.

Andrés Segovia died June 2, 1987, in Madrid, Spain, leaving a profound mark on the guitar world. His dedication, passion, and transformative influence have solidified his place as a true legend in classical guitar.

Conclusions

Talking about Segovia requires a lot of space, and one cannot focus on all aspects of his art. My goal was to address some elements that have too often been misunderstood or misinterpreted. I will undoubtedly return to write articles regarding his style concerning specific composers, focusing more on the essential details.

For now, I can only invite all music lovers to listen to Segovia’s varied recordings, enjoy his extraordinary timbre, and ultimately appreciate the work done to enhance the guitar far beyond all possible expectations.

Of course, I will gladly answer your questions and comments so that the master’s memory remains alive. Beyond the fact that many of his most faithful pupils have perhaps (as is usual) surpassed their mentor, this does not imply that his interpretations should fall into oblivion. Every guitarist should listen to him, possibly together with Williams, Fisk, Bream, etc., precisely to broaden one’s horizons and to be able to grasp all those nuances that make the guitar a wonderful (and who knows, unparalleled) musical instrument!

I also want to share the Spotify playlist with many of Segovia’s recordings so you can immediately start enjoying them:

If you like this poem, you can always donate to support my activity! One coffee is enough! And don’t forget to subscribe to my weekly newsletter!