Is there a relationship between music and poetry? Indeed, this is a somewhat partisan question and can be answered in many ways. In principle, all art forms can be related to each other, but that is not what I would like to discuss. My question implies a condition widely verified in everyday reality: pop music and songs.

The uniqueness of the musical experience in the context of song

We are used to listening to “songs,” not music with lyrics (conversely, lyrics accompanied by music). In other words, our way of perceiving and remembering is not based on decomposing constituent elements but on their synthesis. It is true that there are covers and even harmonic and melodic reworkings, but this does not help much. The results, in fact, are “reunified” in a union that appears inseparable.

Indeed, it is possible to make aesthetic judgments and appreciate or despise a given achievement, but we rarely read “biased” criticism except to emphasize specific intrinsic properties. For example, we can say that the lyrics of a song are beautiful while the music is ugly, but while this apparently seems the result of a split in the analysis, in truth, the origin from which the judgment takes shape is always the song, as a unified and cohesive form of expression.

But let’s admit that such an analysis is actually possible: the problem, far from being solved, has only moved into far more rugged territory. Indeed, how can one say that a particular musical composition suits a particular poetic text? Conversely, given a poem (i.e., the lyrics of a song), how can it be argued that a particular music and not another well represents it?

Music as an asemantic language

While I do not agree with all of Eduard Hanslick’s thinking (ed. see note at the end of the article), I am convinced that music can, at best, be defined as an asemantic language, i.e., one based only on form (i.e., syntax) and its beauty exists solely in the unfolding of it during an instrumental performance. In this sense, the heart of Romantic thought favors absolute music not so much because it dislikes singing but because music is an art form that cannot be enriched through contact with the poetic world.

To give a practical example, we can think of a generic verse,“The sky is blue.” Is it possible to express this concept in music? Not, since no melodic, harmonic, or timbral form can denote anything. So why do we think a relaxed composition with long, sustained notes expresses poetic verse better than a fast rhythm, perhaps even based on wide harmonic intervals?

Music, poetry, and imagination

The answer to the above question is by no means trivial but indeed contains within itself both a conventional element (i.e., we are accustomed to making specific associations and rejecting others) and one of a purely cognitive nature. It cannot, in fact, be ignored that whatever signal reaches our brain is processed through associative mnemonic processes.

Laymen need not fear: beyond technicalities that will not be considered here, it is sufficient to point out the evocative power of images, words, sounds, etc. It is much more common than people think. Who has never said or thought, at least once, that a painting, a glimpse, or a song reminded them of past experiences?

In fact, it is possible to speak of musical imagination only from a reality encompassing several elements and is most likely based on the existence of a language capable of denoting and processing the concepts themselves in an abstract way. Consequently, a human being, from the moment he or she begins to take in and store external experiences and signals without any will, also begins to “imagine,” “associate,” and ultimately be able to judge beautiful (or good, pleasant, etc.) the juxtaposition of a relaxed melody with the image of a blue sky and ugly the other way around.

Of course, when I speak of “imagining,” I do not mean just the retrieval of a pseudo-image (somewhat as a generative artificial intelligence would do), but the semantic elaboration of a kind of description that, far from remaining intact, frays in various directions, bringing attention first to one element, then to another, and so on. If this process “stumbles” into a particular semantic place (e.g., meeting the partner in one’s life), the emphasis magnifies the perception with a resonance mechanism.

Imagination cannot justify aesthetic value

Unfortunately, even if imagination is a common and, in some ways, intersubjective process (i.e., shareable while remaining subjective), this does not imply that one can base the aesthetics of a juxtaposition of music and poetry on evocative power. First, as mentioned above, evocations are subjective and, more importantly, based on a semantic language that plays the role of mediator.

Since music does not possess semantics, it cannot be structured with an objective purpose unless one resorts to imitation (e.g., the crowing of a rooster or the ticking of a clock) or to all possible notes (titles, subtitles, programs) that guide the listener toward a specific decoding of the sound material.

The best example of this is Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony, which, far from being “pure” music, has a subtitle crucial to its understanding:“Symphony of Destiny“. Beyond the history of the composer and his vicissitudes, the listener is informed beforehand that the musical theme is based on the concept of “destiny.” Consequently, it is sufficient to listen to the opening motif to “block” the imagination and guide decoding to an area where the features of destiny can be found.

The sudden appearance of the “chime” or “act of knocking” appears as a presentation of fate itself (little matter if one immediately thinks of a visitor knocking at the door) and activates in each heart all the mental processes that evoke the appearance of the unexpected (beautiful or ugly), surprise and the inescapable. The repetition of the theme in the subsequent movements, though varied, always provides a reference to the initial idea, but perhaps, through tempo, melodic, harmonic, and rhythmic choices, Beethoven was also able to allow for different mental associations.

Perhaps the first impact may be dramatic and violent, as it is from a musical point of view. Still, subsequent processing becomes increasingly calm, resigned, aware, and ultimately benevolent toward what immediately appeared as an unexpected and unwelcome guest. As a result, the mental images elicited in the listener also undergo a metamorphosis and, depending on the case, may shift from unpleasant memories to calmer, even fulfilling moments.

There is no music for a poem or poetry for a musical composition.

Notwithstanding the above, the initial problem remains unchanged. Music (not a motif, but rather an entire unfolding) can never be called “right” or “wrong,” depending on the poetic context being addressed. It is true, for example, that a melancholy song will probably use minor keys and particular dissonant chords extensively, but this choice does not arise from a search for correspondence between poetic context and music but rather from convention.

Neuroscience, before musicology, should investigate why a minor key elicits calm, sad, or reflective images while a major key is perceived as more cheerful and jaunty. Certainly, we can say that the link does not lie in language unless (a fact that I personally have not ascertained) music, from its historically documented origins, has always relied on the forced choice of minor keys for sad songs (e.g., the “Miserere” or the “Kyrie Eleison” in a mass). At the same time, it chose major keys for dances and songs that hymned pleasant realities.

Beyond these considerations, the articulation of a composition still remains outside any context of analysis. There are thousands of pieces in the minor key, but Bach chose only one, for example, for the chorale of one of his cantatas. Why? Here, we return to the initial question: is there a relationship between music and poetry?

The answer, as disappointing as it may seem, is no. There is no relationship beyond whether or not music needs to enrich itself through contact with other art forms. Any musical choice from a text can undoubtedly build on its themes and extensively use compositional tools to emphasize a verse, repeat it polyphonically as if to echo it, and so on. But this is not enough to say that you are composing the “right” music for a specific poetic text. Besides, one only has to listen to masses composed over the centuries by different musicians to understand that there is no “correctness” in Händel ‘s Hallelujah compared to that set to music by dozens of other composers.

In conclusion, I would like to emphasize the need to rethink the relationship between music and poetry, starting not from the idea of a natural “marriage” but rather from the importance that this de facto relationship has always had. Even if no form of musical composition is “aware” of the poetic context of reference, this does not detract from the fact that specific results have a far more significant aesthetic impact than others.

The authors’ task, then, should be to transcend the limit of the customary to explore varied territories that can activate more and more mental associations in different listeners. That is, contemporary music should expand more, reacquainting itself with the complex forms of classicism (such as the symphony), but, at the same time, translating them into an entirely different socio-historical context. The journey is long, but the possibilities are great, and creativity, fortunately, knows no space-time limit.

Brief note on the musicological thought of Eduard Hanslick

Eduard Hanslick, a prominent 19th-century music critic and aesthetician, profoundly impacted how music was perceived and understood in his time. Hanslick conceived music not only as a means of emotional expression but as an art form that should be appreciated for its inherent beauty and structure. He believed that the beauty of music lay in its composition, form, and structure rather than in any extramusical narrative or emotion it might convey.

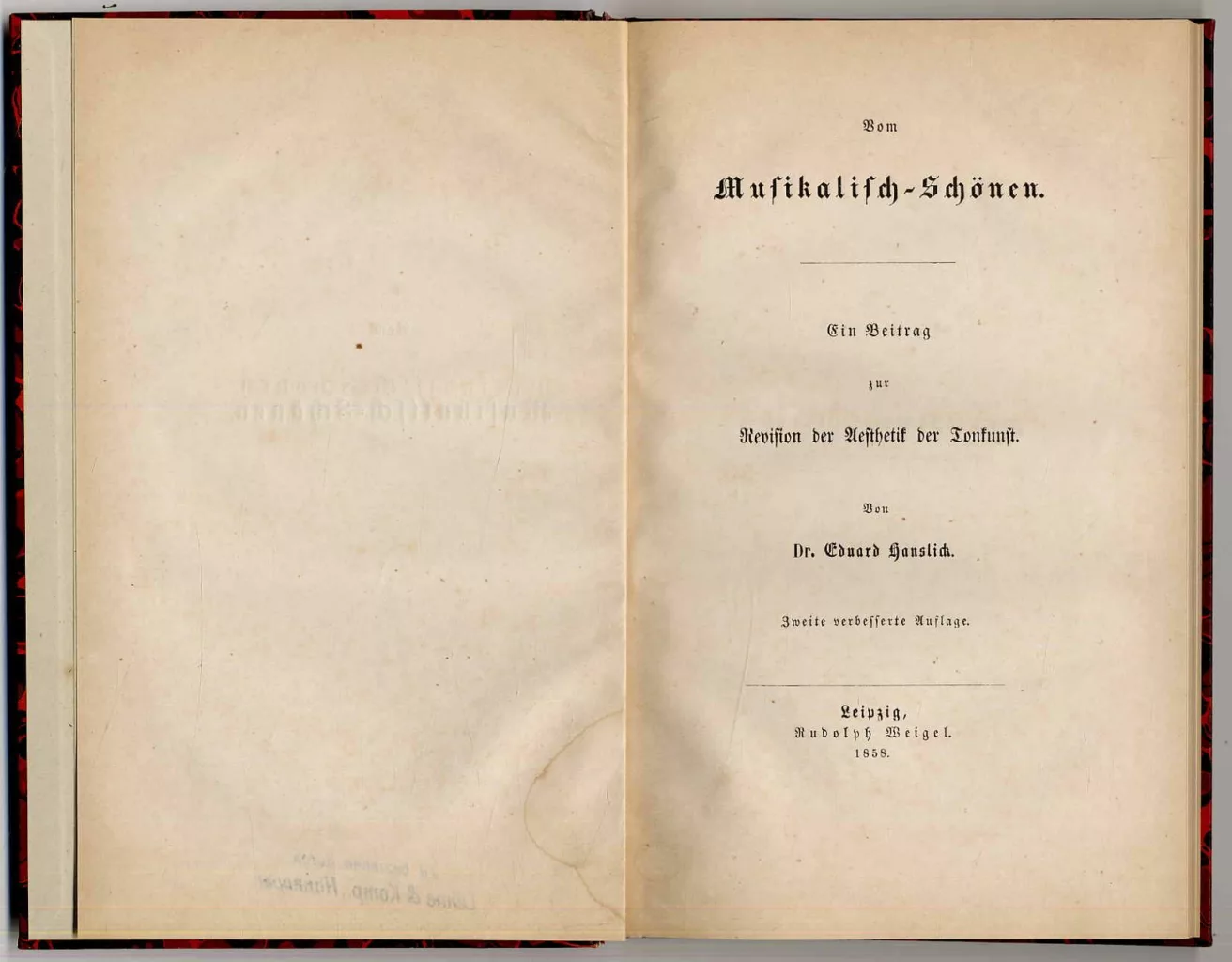

One of the main results of Hanslick’s work was his emphasis on the formal elements of music, particularly in his book“Vom Musikalisch-Schönen” (in English published under the title “On the Musically Beautiful“). He argued that the value of music should be judged on its formal qualities, such as melody, harmony, rhythm, and pitch, rather than on subjective emotional responses.

This idea sparked a debate between proponents of program music, such as Richard Wagner, and proponents of absolute music, such as Johannes Brahms, shaping the discourse on musical aesthetics for years to come. Hanslick’s legacy continues to influence music criticism and analysis to this day.

If you like this post, you can always donate to support my activity! One coffee is enough!