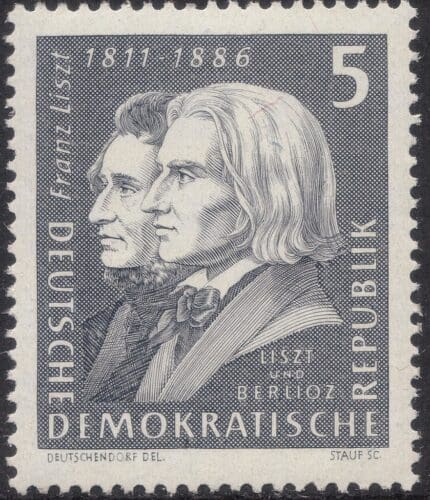

There’s no denying it: Romantic composers never cease to amaze us with their modernity, so much for the unchanging persistence of music composed before a specific historical period (a fixed idea of many music lovers and conductors today). For example, Franz Liszt (1811 – 1886), in addition to his religious vows, had also embraced social, artistic, and political progressivism to put even Marx to shame!

The music of the time, with the legacy of the classics (in particular, Haydn and Mozart) and pre-romantic (i.e., Beethoven), now seemed burdened with a mortgage burden that was almost impossible to liquidate. Yet many theatergoers of the time were beginning to dislike the constant references to the past and unwillingly paid for theater tickets when the programs did not promise at least a few surprises.

Yesterday, today, and tomorrow

This was before the term “classical music” was coined to refer to a sequence of “bodies” on display. I know the phrase is a bit heavy-handed and, indeed, not disparaging in nature (me being the first admirer). Still, the bitter truth is that if Franz Listz looked to the masses, stratified into social classes dictated, not by appointments and investitures, but rather by the pressing industrial power that spread like wildfire, we (about 150 years after his death) look to his stereotype, as the only source of “cultured” music worth listening to.

The trouble, as is easy to guess, is that social classes are not only not dead (i.e., communism only whitewashed facades and fattened oligarchs) but have put down deep roots, especially socio-culturally. By this, I do not mean that the nineteenth-century workers were educated; on the contrary, likely, the bourgeoisie did not care much for culture either, but the problem is that if the “Paganini” of the piano considered the elites of the time as deleterious, today he would end up taking refuge in a Pacific atoll in order not to realize how obtuse and short-sighted evolution has been.

Because evolution has (inevitably) taken place, and we have already talked about the dominance gained by pop music, one has to ask: Is this really what Listz so desired? He often spoke of “musical progress,” marking with as much emphasis as possible the ever-changing reality to which art had to relate. He observed the birth and growth of an industrial society, where the strong powers were not the aristocrats but lay like lapdogs at the feet of bankers and captains of industry.

When it is a composer from the past who sees the future

In other words, Franz Liszt understood two basic things well: first, that music lovers were no longer to be sought within the drawing rooms, and second, that music not palatable to the working-class and lower-middle-class masses was doomed to fail its purpose. Reading the theater programs in 2024, we can undoubtedly say, “Poor deluded!”

Not only did his idea drift further and further away from “consumer” music (the kind he wished for when he hoped the songs would be sung by workers, office workers, and managers), but it also foundered against much sharper rocks. If Liszt saw the marriage of music and poetry as the crowning glory of an artistic endeavor aimed at representing society in a comprehensive and, above all, engaging way, we might ask what became of his purpose and wish.

The answer is at least as simple as the result: pop music has taken the place that the “great” composers guarded, while a parallel branch, with the features of an Egyptian mummy, has crystallized in a pose that recalls a perennial déjà-vu. Truncated by an inflated nothingness like Zeppelin, artistic directors of theaters and conductors of related orchestras announce with smiles that they will usher in the new symphonic year with Schumann’s music.

So much for the intentions of poor Liszt, who wanted mass dissemination, the breaking down of all elitist boundaries, the representation of popular culture, and so on! While Spotify broadcasts music written the day before, they, in fancy dress, sing (rightly) the praises of Brahms, Beethoven, and Mozart, oblivious to the fact that some 200 years have passed since their last work.

Evolving arts versus “corpse” music

Does it mean that they must fall into oblivion? Never! This would be silly before it is even irreverent. It is as if Picasso had overshadowed Michelangelo or Raphael, De Chirico had made people forget Giotto, or Pirandello had ridiculed Boccaccio or Shakespeare. But after this slew of comparisons, a question timidly arises: why is Picasso held in such high regard? Why is the prose play “Six Characters in Search of an Author” considered a masterpiece? Why is Frank Lloyd Wright’s “House on the Waterfall” hailed on par (or nearly so) with St. Peter’s dome?

Interesting questions, aren’t they? The usual consequence is to ask, why, in music, is Bob Dylan considered a dwarf in front of Schubert? Why is Morricone, much treated as a film composer, charming, but who cannot hold a candle to Mahler? In short, why did all the arts follow Franz Liszt’s invitation and “cultured” music, the first recipient of his words, self-segregate into a museum of anatomy and paleontology?

I believe the reason is simple. “Popular” music has followed the course of events, updated itself continuously, experimenting and constantly seeking new ways of expression. In a sense, Liszt’s hope of hearing the songs among the crowds of workers was crowned. But then, why complain? Unfortunately, the composer does not clarify that the marriage of music and poetry must marry musical engagement with poetic engagement. “Commitment,” meaning the pursuit of quality through true spiritual inspiration.

Indeed, this has happened in many cases, especially from a poetic point of view, because several pop and rock song lyrics are dense in content and pleasing to even the most refined palates. Unfortunately, however, the music and many song lyrics at the top of the charts can be classified as examples of the exercise of stupidity! Most seriously, the record industry (analogous to the same society deprecated and condemned by Liszt), in fostering craftsmanship with low pretensions, feeds the so-called “mainstream,” supporting, willy-nilly, the cause of the nostalgics of classicism.

Conclusions

Whose fault is it then (if fault it is)? Indeed, we can immediately exonerate classical and romantic composers and, in a sense, “pardon” Chopin’s lovers and Haydn’s oratorios. Indeed, there is no reason to blame those who reject the ugly. As I have already had to say, if it is indispensable to find a scapegoat, the only “culprits” are precisely contemporary composers.

So much for Liszt’s rave praise addressed to the Marseillaise! The unhealthy idea of intellectualistic music, chained by conceptions that cannot be decoded without repeated explanation, and the rejection of the”mainstream” have contributed to letting all the romantic virtuoso’s vague ambitions fall into vain. Taylor Swift certainly does not need Caroline Shaw, and the latter can follow her ideas by giving up the luxurious life of rappers who think they are the new Dante Alighieri! In short, no one needs the other in an unparalleled circle of “selfishness.”

We are, therefore, in an impasse that seems to have no way out. Yet the solution is straightforward: poets (please, let’s not call them “lyricists”) could start writing lyrics suitable for music, and, even not imitating the concept of total art advocated by Wagner, pop composers could start restudying harmony and composing music, based yes on modern instruments (with much-appreciated “intromissions” of strings, flutes, harps, etc.), but worthy of being juxtaposed with Schubert’s Lieder or Faurè’s songs.

In short, Franz Liszt’s lesson is elementary: music must be progressive because society is perpetually evolving, and any form of conservatism is not only detrimental but completely unnecessary. In addition, music-goers, as is the case today, are also the people sitting and waiting in barbers’ and hairdressers’ salons, and, to put it bluntly, given the massive difference in numbers, it is precisely the latter who should be the privileged recipients of good music, not just those who pay for tickets to sit in half-empty concert halls listening to Beethoven’s Razumovsky quartets.

Never forget the past, then, and never think that Bach or Mozart wrote perishable music. However, time can neither be stopped nor slowed down, so let us try to follow Listz’s example and stop compartmentalizing for “connoisseurs.” Far too many works of art (for connoisseurs) rot in museum cellars. It is time to avoid such waste and not let the industry dictate its standards because usability is not birthed by triviality but by sheer quality art!

Brief biographical note on Franz Liszt

Franz Liszt (1811 – 1886), Hungarian composer, virtuoso pianist, and conductor, was one of the most influential musicians of the Romantic era. Liszt’s significant musical contributions include his innovative piano compositions that expanded the boundaries of progressions and traditional harmonic forms. His works, such as the “Transcendental Studies” and “Hungarian Rhapsodies,” are known for their technical brilliance and emotional depth.

Besides his musical genius, Liszt was also a key figure in developing the symphonic poem, a form in which a non-musical work, such as a poem or painting, inspires a piece of instrumental music. Liszt’s symphonic poems, such as “Les Preludes” and “Mazeppa,” showcased his ability to evoke vivid images and narratives through music.

In addition to his musical contributions, Liszt was known for his philosophical works on music and art. He championed the idea of “program music,” in which instrumental music conveys a narrative or extra-musical idea, paving the way for composers such as Richard Strauss and Gustav Mahler. Franz Liszt’s legacy as a composer, pianist, and thinker continues to influence musicians and music lovers worldwide.

If you like this post, you can always donate to support my activity! One coffee is enough! And don’t forget to subscribe to my weekly newsletter!